TOLEDO’S DAY IN THE SUN

An Account of the 1919 Dempsey-Willard Prizefight

By Willis Stork, former Toledoan

Pasadena, California Polytechnic School

During the closing hours of June, 1919, a Great Lakes heat wave slowly settled upon Toledo, Ohio. Without respite for the next few days the mid-summer sun poured down its searing rays and in doing so raised the temperature each day until Toledo and its thousands of visitors together melted on one of the hottest Fourth of Julys on record.

A few months before this meteorological phenomenon, another heat wave was incited which was destined to reach its peak as insistently and relentlessly on that same Fourth of July, and with these two and the effect of the one upon the other lies a story, -- the story of Toledo’s Day in the Sun.

Into the doldrums occasioned by the ending of the war six months earlier and into an atmosphere jaded no doubt by resignation to the recently-enacted Prohibition Act, Tex Rickard tossed an announcement that got a reaction like a spark in a tinderbox. Over all press wires the word went out that at last this country was to have staged a world’s heavyweight championship bout, at Toledo, Ohio, on July 4, 1919. The news was accepted with feeling, sometimes mixed feeling, but at least with feeling everywhere, but in Toledo it set off a wave of excitement that was agitated by single and later organize voices of opposition, that was fanned by the age-old picture of a David-Goliath struggle, that was abetted by the reality of the erection on the north part of the city of an arena larger than ever before constructed by man, that was enlivened by the prospect of history’s first $1, 000,000 gate, that was added to by the flood of copy turned out by a galaxy of sportswriters, cartoonists, and ex-pugilists now turned newspapermen, and that was, above all, fed with the awesome realization that this was happening to Toledo; that at last this little lake port was to become the cynosure of the world’s eyes.

Jess Willard won the world’s heavyweight championship by knocking out Jack Johnson in the twenty-sixth round of a scheduled 45-round bout fought in Havana on April 5, 1915. Johnson, who had gone to Australia in 1908 to take the title from Tom Burns, had proved to be one of the greatest fighters of all time, -- in the ring, that is, but his personal life had become so seamy that members of both races acciduously tried to find a contender good enough to blast the title away from him. In particular, there arose a search for a “white hope,” but the crowd of contenders was a miserable outfit, few of whom wanted, even if they could, to meet the champion. Those who did were either toyed with or, like Stan Ketchel, were brutally laid out on the floor minus senses and front teeth.

The search for a challenger became so insistent and desperate that Jim Jeffries, who had given up the gloves and the title five years earlier, was prevailed upon to meet Johnson. The memorable fight took place in Reno on Independence Day, 1910. Spurred by the wishful thinking that Jeffries would regain his title, the battle was widely publicized and became one of the first big-purse, big-gate fights that led to the golden era of boxing. But the enthusiasm of the boxing world was little compensation for the debilitation that age and inactivity had worked on Jeffries; had he been in his prime, it is doubtful that he could have match Johnson either as a puncher or as a boxer; as it was, he, and the hopes of the boxing fans and writers, took an agonizingly painful defeat.

Johnson,

who had become persona non grata with the Federal authorities over some

of his extra-ring activities, decided it would be healthier to be out of their

reach and took up exile in Paris.

Stories of his riotous living and brash contempt for the proprieties of

life made it even more imperative that the title be returned to respectability

and to the United States. In the search

that ensued, the mantle of the “white hope” was thrust on a colossal Kansan who

had lived an uneventful and, happily, an untarnished life. As a boxer, Jess Willard had a mediocre

record, but that as with everything else was dwarfed by his gigantic bulk; his

six-foot, seven-inch frame, carrying 250 ponds of well-distributed flesh, was

ample on which to pin the hopes for a new champion.

In the meantime, if one thing had become more dissipated than Johnson, it was his fortune. Although not broke enough to risk facing the immigration authorities, he was willing to meet Willard at a place accessible to American fans and money but safe from the arm of the Federal law. After a passing consideration of a Mexican site, Havana, Cuba, was selected.

The result of the bout satisfied everyone; Johnson got his money, Willard got the title, and the American people had a new champion, white, clean-cut, and unimaginably heroic in his proportions.

The surge of joy that swept the country at Willard’s unexpected victory made his return a triumphal journey; overnight he was catapulted to fame, popularity, and even hero-worship. But none was to last for long. When the title changed from Johnson to Willard, it had gone from one extreme to another, from one as flamboyantly colorful as the other was drearily colorless. Willard had no interest in boxing other than the means it represented for getting money; certainly he was no fighter. More to his liking was the cowboy role which had rather synthetically been built around him as a title contender, and once he had the championship he appeared in circuses in that role and finally organized his own Wild West show. It was almost a year before he again entered the ring; this time in New York City where he methodically used his long reach to keep Frank Moran from landing his famed “Mary Ann,” a hitherto highly effective bolo-like right. Although a no-decision bout, the newspapers conceded that Willard’s bulk had given him the edge in the dull ten-round affair. No one, least of all Willard, seemed interested in promoting another fight, so the champion went back to his Western show for another three years.

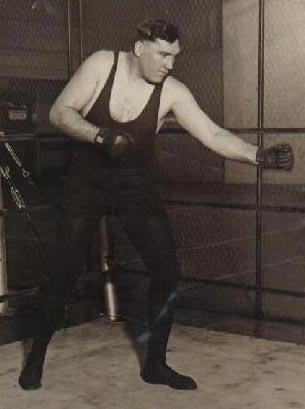

While Willard was resting happily in this pugilistic lethargy, something was beginning which was ultimately destined to bring him back to the squared ring. For out of the West came riding an American young Lockinvar. He was not white-plumed, but was dark in complexion and beard; he rode no prancing steed, but made his way by riding the rods; he was battling for no lady’s hand, just for a handout. He was a surly, lashing fighter, call Jack Dempsey.

Born of a poor but religious Mormon family, Dempsey was christened William Harrison, but he replaced that with “Jack” (after the famous middleweight champion, Jack Dempsey, “The Nonpareil”) as he emerged from a knock-about roustabout into a one-round knockout specialist.

Hopping

freight trains from job to job, from fight to fight, picking up and dropping

managers, working as sparring partners, lean, sometimes hungry, scowling and

black-browed, young Dempsey began to make the fistic world take notice. He was serious about the fight game,

maintained his own training rules, and tried to learn pointers from every

manager and opponent he met. Although

he quickly liquidated most of his adversaries in the Rocky Mountain and Pacific

Coast area, Dempsey’s several trips East brought little advancement. As he states in his autobiography, Round

by Round, “A fighter has to have a manager.” And get a manager, he did.

When he teamed up with Jack Kearns, it was the beginning of one of the

most fabulous fighter-manager tie-ups in history. With nothing in writing, the partnership eventually built up to a

million-dollar enterprise.

Hopping

freight trains from job to job, from fight to fight, picking up and dropping

managers, working as sparring partners, lean, sometimes hungry, scowling and

black-browed, young Dempsey began to make the fistic world take notice. He was serious about the fight game,

maintained his own training rules, and tried to learn pointers from every

manager and opponent he met. Although

he quickly liquidated most of his adversaries in the Rocky Mountain and Pacific

Coast area, Dempsey’s several trips East brought little advancement. As he states in his autobiography, Round

by Round, “A fighter has to have a manager.” And get a manager, he did.

When he teamed up with Jack Kearns, it was the beginning of one of the

most fabulous fighter-manager tie-ups in history. With nothing in writing, the partnership eventually built up to a

million-dollar enterprise.

Kearns, a one-time fighter, was a sharpie, who knew all of the angles: how to get publicity, how to deal with shrewd promoters, how to give his tough young slugger some polish in and out of the ring, how to pick the right opponent for the right time in the climb toward the top. By adroit ballyhoo, Kearns pushed Dempsey in the field of heavyweight contenders, and in a series of bruising knockouts Dempsey upheld his end by eliminating his rivals. In 1918 he scored eighteen knockouts, qualifying him not only for Kearns’ sobriquet, “Jack, the giant-killer,” but also for a chance at Willard’s dusty crown.

Now was the opportune time for another of boxing’s greats, Tex Rickard, to appear on the scene. Bret Harte might well have used Rickard as a prototype for some of his characters, for he was an adventurer supreme. At one time or another he was a cowboy, a rancher, a town marshal, a gambling house operator, a gold prospector, and a beef baron, and his operations ranged from the mountains of Alaska to the plains of South America. He made and lost several sizable fortunes. No matter what he did, he was always a showman and a promoter, and thus his particular talents drew him to boxing, a sport that he made both respectable and lucrative. He is the father of the Golden Age of Boxing.

His first brush with the fight game was in 1906 when he successfully handled the promotion for the Gans-Nelson lightweight title fight for a group of Nevada businessmen. In 1910 on his own responsibility he promoted the Jeffries-Johnson title fight. In this, he guaranteed the principals the unheard-of sum of $101,000, and he made money. Rickard’s preeminence in boxing circles grew until in 1919 he probably was the only man in the world who could have brought about a heavyweight title match. His inducement to Willard was a $100,000 guarantee; to Dempsey a crack at the championship.

With his fighters signed, Rickard had to find a place to hold the match. Boxing was banned in New York and many other states. The reformers who had brought in Prohibition had pretty well put boxing, or prize fighting as the preferred to call it, under their thumb. Overtures from Canada, Mexico, and Cuba were made for the clash, but Rickard wanted it in this country, and he looked about for a permissive spot. Ad Thacher, a Toledo contractor, politician, and boxing enthusiast, got to Rickard and sold him on the strategic location of Toledo and its railroad accessibility to Detroit, Chicago, New York, St. Louis, Philadelphia, and other populous centers.

So it was decided, and so it was announced.

The enthusiasm which the announcement set off was immediately tempered by an aroused opposition. One church association registered a vigorous protest claiming that the “prize fight will bring into our borders hordes of the lawless and vicious elements, that it will stimulate gambling on a vast scale, and sanction brutality, and that it will denigrate the fair name of Toledo in the eyes of the rest of the nation to the low level of Reno as a wide-open town.” As far away as Cleveland the Ministerial Union voted unanimously to protest to the governor against the match as a menace to public morals. The Toledo Ministerial Union sought unsuccessfully to secure a permanent injunction against the promoters. The Sunday School Association passed a resolution of opposition pointing out that the fight would bring to Toledo “thousand of criminals, prostitutes, and gamblers whole presence in any city is demoralizing, and whose influence on the youth of the community is a pollution. No single thing could injure the good name of a city more than to be known as a place where a national prize fight was pulled off.” The Women’s Christian Temperance Union asked that “all influence be brought to bear to protect our city form this disgrace.”

From the outside, professional obstructionists were brought in. Dr. Wilbur Crafts, superintendent of the International Reform Bureau, came from Washington to stop the bout, claiming that he had prevented the Willard-Johnson fight from being held in Florida and also had put the skids under a match between Jeffries and Fitzsimmons.

Mayor Cornell Schreiber was besieged by protests, petitions, and injunctions to forestall the fight; finally he was driven to issue a long public statement supporting the event. In his proclamation he pointed out that the location of Toledo and its railroad accessibility to Detroit, Chicago, New York, St. Louis, Philadelphia, and other populous centers.

So it was enthusiasm which the announcement set off was immediately tempered by an aroused opposition. One church association registered a vigorous protest claiming that the “prize fight will bring into our borders hordes of the lawless and vicious elements, that it will stimulate gambling on a vast scale, and sanction brutality, and that it will denigrate the fair name of Toledo in the eyes of the rest of the nation to the low level of Reno as a wide-open town.” As far away as Cleveland the Ministerial Union voted unanimously to protest to the governor against the match as a menace to public morals. The Toledo Ministerial Union sought unsuccessfully to secure a permanent in injunction against the promoters. The Sunday School Association passed a resolution of opposition pointing out that the fight would bring to Toledo “thousands of criminals, prostitutes, and gamblers whose presence in any city is demoralizing, and whose influence on the youth of the community is a pollution. No single thing could injure the good name of a city more than to be known as a place where a national prize fight was pulled off.” The Women’s Christian Temperance Union asked that “all influence be brought to bear to protect our city from this disgrace.”

From the outside, professional obstructionists were brought in. Dr. Wilbur Crafts, superintendent of the International Reform Bureau, came from Washington to stop the bout, claiming that he had prevented the Willard-Johnson fight from being held in Florida and also had put the skids under a match between Jeffries and Fitzsimmons.

Mayor Cornell Schreiber was besieged by protests, petitions, and injunctions to forestall the fight; finally he was driven to issue a long public statement supporting the event. In his proclamation he pointed out that the government has used boxing in conditioning soldiers during the war, that the boxing “exhibition” would be limited to twelve rounds, that seven percent of the gross receipts would go to Toledo charities, that tens of thousands of visitors would be spending thousands of dollars in Toledo, that the city’s natural and industrial advantages would be brought to the entire world, and (with a remarkable lack of foresight) that the bout would be conducted strictly as a “scientific boxing match.”

Although Rickard issued a statement that it was “time to squelch these so-called reformers who have made a nuisance of themselves,” the opposition was not giving up that easily; now it turned to the governor of the state. One minister charged, “The governor has power to stop it if the mayor does not. Everybody interested in the fair name of the city should write the governor to save the city and the state from this disgrace.” Some have it that Addison Thacher got to Governor Cox first. Regardless he tried to sidestep the issue, stating that the law prohibited prize fighting, but permitted boxing contest, and that the interpretation of the law rested with the local authorities. Robert Dunn, a state representative, tried to get a bill through the legislature placing the authority directly in the governor’s hands but it was defeated. Having been taken off the hook, the governor came forth with this noble statement, “Several attempts within the past few weeks were made in the Ohio legislature to change existing statues on the subject, but without result. Failing in this, one branch passed a resolution requesting me to interfere with the contest. In other words after the assembly itself failed to give me legal authority, one branch urged me to proceed without right…. If the law is changed, giving me the right of interference, it will be exercised, but I shall not meet hypocrisy with usurpation of power.”

For some unaccountable reason, the Toledo papers took no stand on the controversy; as far as the editorial columns were concerned no one would have guessed that one of the century’s great sport events was about to be staged locally. However the New York Times was moved to write, “A few years ago no one would ever dream that any city in this country would have developed the broad point of view which permits this greatest of ring contest.”

If all this fuss about staging the fight bothered Rickard, it was not noticeable. One of his backers, Frank Flournoy, a sportsman he had met in the cattle business in Argentina, came from Memphis with $150,000 and opened up a business office. An experienced ticket salesman was brought from New York to handle that end of the operation.

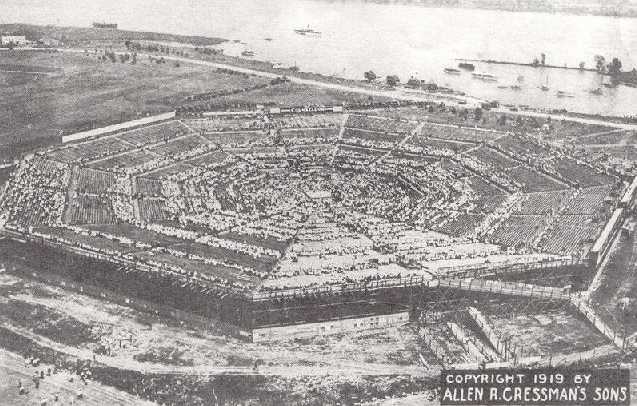

On May 15 the construction of the arena was begun in 60-acre Bay View Park, about four miles north of the heart of Toledo. The park, overlooking Maumee Bay, an inlet of Lake Erie, was level and unobstructed, unless millions of dandelions could be considered an obstruction. Rickard called upon James McLaughlin, a San Francisco, engineer, who had built other arenas for him, to do the construction. It was first planned for thirty thousand, but before construction began it was enlarged to 50,000. It was later extended to a seating capacity of 80,000, with a possibility by a little crowding here and there and including standees to reach a total capacity of 100,000. People really began to take notice when it was pointed out that the arena would exceed in size the Yale Bowl, until then the world’s largest.

McLaughlin rounded up 300 carpenters (at a princely salary of $5.60 for an eight-hour day) and put them to work constructing the huge octagon out of 1,750,000 feet of Michigan white pine. From his past experience McLaughlin had some definite ideas about just how one of these bowls should be built. He eschewed the use of bolts, relying entirely on nails, using 50,000 pounds or approximately two carloads. No stairs were allowed, only ramps with inclines so gradual that no danger was involved. In fact, McLaughlin took every precaution possible; one of his previous arenas had been a rather shaky structure, and he was not taking any chances this time. As insurance against any settling should rainy weather appear on the day of the match, or even a few days before, heavier footings were used although it cost him an extra $3,500. The carrying capacity of the lumber and the tensile strength of the nails were carefully determined and a margin allowed for safety. Although the structure was originally planned for 50,000 persons, a total of 80,000 spectators was taken as the basis for the “load” estimate, and instead of allowing the standard 175 pounds per person, an average of 200 pounds was taken. This gave a “live load” of 8,000 tons, but to allow even a further margin of safety, actual construction was based upon a load of 10,000 tons. The 600-foot diameter of the bowl meant that no seat would be farther than 290 feet from the ringside. These outside seats would be thirty-four feet from the ground and reached by a runway 180 feet long with a scarcely noticeable grade of one foot to every six feet. An allowance of eighteen inches seatway on a ten-inch plank was allowed for each ticketholder. The only concession granted the higher-priced seats was eight inches more legroom.

Rickard, who followed the construction of the arena with dogged interest, had an inspiration which was accepted by contractor McLaughlin; by applying a few of the well-known rules of mathematics, he discovered that by reducing the size of the ring from 24 feet to 20, a total of 176 square feet could be saved, or, more important still, two more rows of ringside seats could be added. Kearns accepted the change with complete equanimity, stating, “Why Jack could meet Willard in a 10-foot ring with bare fists, if necessary. He is not going to try to get away from Jess when they meet and you can lay to that.”

Remembering a sad and costly experience at Reno where 2,000 spectators climbed the fence to see the Jeffries-Johnson fight for free, McLaughlin set up supposedly impregnable precautions against rushing. Eighty feet out from the perimeter of the arena he constructed a barbed wire fence eight feet high with a total length of a half-mile. Between this and the stands he built a board fence twelve feet high with a barbed wire topping. As final deterrents, there were a five-foot barbed wire fence on the top outside edge of the arena and a plan for armed guards to be stationed every twenty-five feet.

Late in May both fighters set up training camps on the shores of Maumee Bay. Kearns, Dempsey, and retinue moved into the Overland Club about a mile from the arena. The fourteen-room house had adjoining facilities for boating, fishing, and bathing. Also on the grounds was a roadway over which the challenger took his daily ten-mile runs. Willard set up his training site in a tree-shaded area on the bank of the bay, but chose to live in town and rented a large residence in Toledo’s fashionable West End.

At both camps the outdoor rings were surrounded by a canvas enclosure for spectators who thronged out from the city for the daily workouts. In the closing days of training as many as 5,000 fans paid an admission fee of fifty cents at each of the centers to see the principals in their final tune-ups.

Due to the long period of relative inactivity in boxing during the war, a serious paucity of able sparring partners plagued both camps. Both Archer, Willard’s business manager, and Kearns made hurried calls on New York for additional heavyweight fodder. In Dempsey’s camp the problem was complicated by the number of the partners calling it quits on the premise that the challenger was inconsiderately dealing out too much lethal punishment to his helpers.

Sunburned and surly, Dempsey was deadly serious about his training, and each time he entered the ring it was as though it were the main event. Assiduously watching every movement was Dempsey’s veteran trainer, Jimmy DeForest, and after each exhibition he held a session with his fighter analyzing the hitting, blocking, feinting, and footwork. After this skull session Dempsey would practice the suggested changes, sometimes for a couple of hours, while DeForest with his everpresent unlit cigar in the corner of his mouth watched and commented.

Nick Albanese, a well-known restaurateur, closed his eating establishment in Columbus to come and prepare meals for Dempsey’s headquarters. Every piece of meat was broiled over a wood fire and before being served was wrapped in a cloth to absorb any grease or fat. Albanese also concocted the pickling brine which Dempsey used on his face to toughen it.

Dempsey stayed close to his camp. In addition to his regular roadwork, he spent his spare time swimming, playing cards, and visiting with his camp crew. Later in his autobiography Dempsey reminisced, “The month of June there on the shore of Lake Erie was as pleasant as any I can remember in my whole life.”

Aside from the throngs of spectators and the lack of sparring partners, the two training camps had little in common. Willard’s workouts were perfunctory. He saw no benefit in using a sparring bag. He did no roadwork; “Long grinds on the road are just the thing for cross-country runners, but who wants to be a cross-country runner when it so happens that one is the heavyweight champion of the world?” He received some support, perhaps tongue-in-cheek, from Ring Lardner on this point of view: “A whole lot of fellow experts has criticized the big fellow on account of him not doing any road work. Well the way I look at it is that when a man is training for a golf match he don’t go out every day and practice skinning the cat on a trapeze and I figure the reason Jess don’t get out and practice running is because he don’t expect to run next Friday.”

Some of Willard’s supporters urged him to hire a competent trainer, but Big Jess was confident he could handle this chore himself and brushed off the suggestion with the comment, “I know how I trained for my fight with Johnson. No one knows better than I how to get myself in the shape I want for the bout. Then why should I hire one, even though he is well known as a trainer, and take a chance on his system?”

Aside from some stunts such as having a sparring partner run at him and butt him in the stomach, Willard did considerable serious training and impressed many of the sports writers with his improved hooks, his speedy countering, and his shortened jolting lunges. His footwork was nothing to rave about, but apparently this was of little concern. One reporter observed, “Hitting Willard on the side of the jaw solidly appears to be next to impossible, due to his rolling his head with the punch. Using his great height to advantage, he either parries or rolls his head to the side and the blow loses its force.”

Willard spent his spare time in town, preferably in the lounge of the Secor Hotel, chatting with friends and greeting strangers. A lady reporter for the local paper gushes, “I have just shaken the hand of Jess Willard, and the handshake of the giant is as sincere, as hearty, and as unaffectedly gladsome as that of a Methodist elder. His famous smile, as inscrutable as that of the Mona Lisa, will, I fear, be the undoing of one William Harrison Dempsey. It is hard enough to meet a scowling antagonist in any encounter, but one that smiles and smiles even when things are going very wrong, well, he’s practically invincible, isn’t he?”

As the date of the fight approached, it provoked one of the greatest conclaves of sportswriters ever assembled. Among the more than 300 newsmen in Toledo were such writing luminaries as Jack Lait, Frank G. Menke, Bat Masterson, Otto Floto, Irvin S. Cobb, Ring Lardner, Damon Runyon, and Grantland Rice. An equally distinguished group of artists and cartoonists included Bob Brinkerhoff, T.A. “Tad” Dorgan, Harold Talburt, Robert Edgrem, Rube Goldberg, and Robert Ripley. As a diversion from covering the training camp sessions and from lobby lounging these gentlemen journeyed to nearby Inverness Club on July 2 to enjoy a special 18-hold golf match arranged by Grantland Rice between humorists Ring Lardner and Rube Coldberg for the “Comedy championship of America and Cuba.”

A more frenzied group included those out-of-towners and local citizens who were scrambling to be cut in on the approaching bonanza by getting a corner on some kind of a concession. One of the more lucrative visions had to do with bedding down the hordes of visitors. All of the hotels made plans to insert extra cots and beds in their rooms. A minimum flat rate of $5.00 a bed prevailed, and some of the larger rooms had as many as twenty cots crowded into them. Ad Thacher rented vacant department store building and filled it with 2500 cots procured from a nearby Army camp. When the fire inspectors decided he could not use the building as a dormitory because it had no fire escapes, he prevailed upon them to lend him a couple of ladders, and he was given the go-ahead. Another enterpriser leased the barn like city market and the Terminal Auditorium and stocked them with 2000 cots. Vacant space throughout the city was rented and advertised with enticements such as “On the ground floor,” “Coolest and best ventilated building in Ohio,” Safe for your valuables,” “For men only,” and “Electric fans running all night.”

Plans for feeding the multitude assumed like proportions. Newspapers reported that hotels and restaurants were doing away with a la carte service in favor of a single bill of fare with a light hike in prices, for example, a fifty cent meal was going to cost a dollar and a half, and the price of a cup of coffee would be ten cents. In addition to a number of impromptu boarding houses, all saloons announced they would be serving meals.

H.M. Broad, a Chicago hot dog king, set up business at the arena three or four days before the bout. He had the sandwich concession and planned on dispensing frankfurters and cheese sandwiches to the curious and hungry visitors at the arena several days before the fight as well as to the giant throng coming for the big show. Broad’s purchases of foodstuffs reached staggering amounts, something like a ton and a half of frankfurters, half a ton of cheese, and many thousand loaves of bread and rolls.

Plans for quenching the thirst on the big day included 3000 gallons of lemonade, 96,000 bottles of pop, and 200,000 bottles of Kovar, a new brand of near beer. The near beer was shipped to a railroad siding at the arena in four cars containing 50,000 bottles each with the reassuring knowledge that a reserve supply was being held in the warehouse if more were needed.

Tremendous supplies of ice cream and cigarettes were ordered as well as such standard items of stadium paraphernalia as cushions, sun shads, and field glasses.

Supposedly one of the best concession items, the official souvenir program, was in the hands of the local newspaper. Surprisingly, the cover of the program made no mention of th4e fact that the engagement was to be a prizefight or that a title was at stake; it was simply titled, “Willard-Dempsey Boxing Exhibition.”

The logistics for handling the crowd involved both extensive and intensive planning. Thirty special trains were scheduled to converge on Toledo from New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Texas, and other distant points. All of the regular trains were to add extra passenger cars. The two Great Lake steamer lines, the D & C and the White Star were booked solid. Dan O’Leary, a veteran pedestrian, and six companions hiked from Chicago in five days flat.

Locally the big problem was to get the fans out to and back from the bout. Street railway officials planned on running 120 cars carrying 15,000 people each hour. The city set aside an area near the arena near the arena for 21, 000 cars a $2.00 for each space. A tug-towed scow was scheduled to leave a downtown pier at 9, 11, and 1 o’clock for a one-hour trip out to the bay site. Nineteen trucks and moving vans were engaged by 400 Chicago businessmen to haul them from the Union Depot to Bay View Park.

Chief Inspector Delehanty of the Toledo Police Department also was making plans for the crowd; 200 world-famous detectives were imported to scrutinize the throngs for known criminals. He was anxious to prevent a recurrence of the wholesale thefts which were committed at the Jeffries-Johnson bout in Reno, where fifteen-bushel baskets full of empty pocketbooks were found after the crowd dispersed.

As the date of the fight approached, a serious problem developed which for a time overshadowed all of the other problems and issues. It was a matter of who would be the third man in the ring. A small army of campaigners patrolled the hotel lobbies and other places where ring followers gathered and loudly extolled the merits of their respective candidates, some of whom were nationally known, more of whom were just “dark horses." Some of the leading contenders were Matt Hinkel, a wealthy sports promoter from Cleveland, William Rocap, sports editor of the Philadelphia Public Ledger, Dick Burke of New Orleans, who was an alternate referee at the Willard-Johnson bout in Havana, ex-champ James Jefferies, and E.W. Dickerson, a former president of the Western Baseball League. Specifications for the job indicated that the referee should be a six-footer, weigh at least 200 pounds, and be “active on his feet.” The compensation was set at $2,500, although ex-lightweight king, Battling Nelson, made an offer, unaccepted, to tackle the job for nothing. Ring Lardner wrote, “Personally I have been asked by Mr. Rickard to referee the fight, but he insists on the referee staying in the ring and I am not going to sacrifice my pride for the man’s whim.”

To get out of the mounting and embarrassing dilemma, Tex Rickard suddenly accepted the suggestion of the Toledo Boxing Commission to use its own referee, Oliver Pecord, and both Willard and Dempsey just as suddenly agreed. Pecord, a 52-year-old former professional baseball player and boxer, had over the previous twenty-five years refereed some 400 fights. Another of the local boxing commission’s regulars, Neecy Weinstein, was named as the official announcer. He was so overcome by the news that he paid $150.00 to insure his foghorn voice, which reputedly could “make telephone wires hum three blocks away.” The remaining officials were ex-boxer Jack Skelley as alternate referee, Tex Rickard and Major A. J. Drexel Biddle as judges, and W. Warren Barbour, later a United States senator, as chief timekeeper.

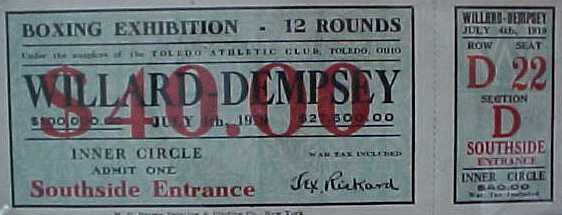

Rickard was optimistic that a million dollars worth of tickets would be sold and he paid a printer $17,000 to produce the ducats ranging in price from $60.00 at the ringside to $10.00 for unreserved bleacher seats. His hopes appeared to be justified when it was reported that a month before the fight advance sales passed the $300,000 mark. One of Rickard’s firm resolves was that none of the tickets should get into the hands of scalpers, and he turned down an offer for $100,000 worth from a New York syndicate. On the other hand he readily sold a block of top-price tickets to the 5,000 members of the Detroit Elks Club who were making the trip to Toledo by boat. A number of fake $60.00 tickets were sold to visitors before the police got busy and put the forgers out of business.

Although it was estimated that $2,000,000 was wagered on the fight, the total amount was not as heavy as might have been expected. Money men did not have too much confidence in either of the participants; Willard has been inactive too long; Dempsey was virtually unknown. Another deterrent on the wagering was that the pari-mutuel establishments were asking ten per cent as a cut instead of the usual three per cent. From day to day the odds shifted, with Willard gaining somewhat as the date approached. He was favored by Wall Street brokers at i7 to 5 on the eve of the fight. Unknown to Dempsey until just before the fight, Kearns had bet $20,000 of the $19,000 guaranteed them at odds of one to ten that Dempsey would dispose of Willard in the first round.

In the few days preceding the fight the most incessant and insidious adversary turned out to be the weather. Day by day the heat and the humidity grew. People started to act strangely. Reporters were thrown out of the training camps. Willard’s sparring partners issued a blanket challenge to Dempsey’s and threatened to invade their camp. Willard announced he would clear all spectators out of his training quarters if they persisted in making so much noise that it interfered with his “thinking.” Rickard began to notice that ticket sales were dwindling off, and he really became concerned when word reached him that the special trains from Philadelphia had been cancelled because of a rumor that Toledo was going to be overcrowded.

Threats that the reformers were going to set the arena on fire forced McLaughlin to hose it down every night and to maintain a phalanx of guards around the clock.

The eve of the fight was the hottest yet. The air was motionless, and it refused to cool down. Therefore when the sun blazed forth the next morning it started out with practically the same sizzling temperature it had left the night before. When the first preliminary bouts started at eleven that morning the mercury had reached a hundred and one and was rising. Most of the early spectators decided to huddle in the shade of the stand rather than suffer in the scorching heat during the interminable preliminary bouts which were being staged every half hour.

As the time of the main event got closer the crowds became thicker. The ringside seats were filled, and the general admission areas were well populated. For the first time in boxing history women had been encouraged to attend, and a special canvas-covered pavilion was provided near the outer reaches of the arena. An estimated 500 women filled this section, and although here and there throughout the big arena there were other women, the majority were relegated to their own special section.

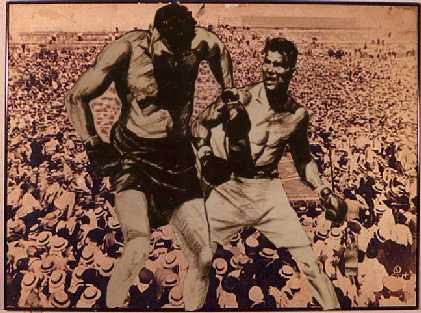

For a final preliminary attraction Major Drexel Biddle had provided a crack bayonet drill squad of sixteen marines from the Philadelphia Navy Yard who gave a spirited exhibition of bayonet thrusts and jabs. The crowd hardly appreciated sitting through such demonstrations in the now hundred fourteen degree heat, and even less so when it became apparent that delay in the main fight would be entailed while a fresh canvas was placed over the ring floor. However, it was hurriedly done, and Dempsey entered the ring first. Mahogany-brown, heavily bearded, and sullen, he received slight response from the crowd. Obviously it was waiting for the champion, and after a deliberate interval, he clambered into the ring. By contrast, he was fair, white-skinned, with his hair neatly trimmed and his face fresh-shaven. He strode to the middle of the ring and with his usual nonchalance surveyed the crowd. His mind was apparently concerned with the impression he was making, and the cheering told him it was good. Towering in the center of the ring, Willard made his already considerable size advantage over the huddled Dempsey sitting in the corner seem even more disparate. Actually the champion outweighed the challenger by sixty pounds and was over six inches taller.

The

fighters were introduced by Weinstein, although he did not announce their

weights. Pecord gave them their

instructions, and they retired to their corners. Barbour, the timekeeper, with his $500.00 stopwatch at hand, was

sitting by the bell. He was ready,

Pecord nodded, and the timekeeper started his watch and pulled the

bellcord. The bell could not be heard,

for in laying the new canvas the rope had become fouled. He tried it again, and there was but the

faintest tinkle. Pecord pulled a

whistle from his pocket, tossed it to Barbour, and shouted for him to use it

instead of the bell. The whistle was

blown, the stopwatches re-started, and the fighters came from their

corners. They approached each other

cautiously. Seemingly Willard was aware

of Dempsey’s past performances in which he traditionally opened with a

ferocious attack, and Big Jess held his left hand out as if ready to ward it

off. Instead, Dempsey circled him in a

crouched, bobbing and weaving style that later was to become his

trademark. Willard began to reach for

him, but the jabs were ineffectual.

Maddened or emboldened he rushed Dempsey to the ropes. Avoiding any of the heavy blows, Dempsey

tied him up in a clinch. Dempsey hoped

he would try it again, and he did. As

Willard rushed, Dempsey ducked under the intended blow and drove his left into

Willard’s stomach. The champion grunted

and started to double over thereby giving an opening for one of the greatest

blows in boxing history. It missed its

intended target, the chin, but landed full force on Willard’s cheek. Not only did it slash his face open and

shatter his jaw, but it did the unbelievable: it toppled the giant to the

canvas for the first knockdown. There

was no neutral-corner rule, and Dempsey hovered over him until the count of

four, when Willard with a look of complete bewilderment got to his feet. Dempsey was fully unleashed now and

proceeded to give what Grantland Rice described as “the greatest exhibition of

mighty hitting anyone has ever seen.”

He flew into Willard as soon as the champion got up, and with a wild

volley of rights and lefts drove him to the canvas again. Dazed but game, Willard got up, only to be

driven down again. This was repeated

seven times in the first round.

On the seventh knockdown, Willard could not get up, Pecord counted to ten, raised Dempsey’s arm in victory, and bedlam broke loose. People crawled into the ring. Kearns and Dempsey started to force their way through the crowd to the dressing room, and the spectators started to file out of the arena. Over the uproar, it started to become apparent that something was wrong, the ring was cleared, and Pecord got word to Kearns to bring Dempsey back. The fight was not over. Barbour had informed the referee that the inaudible whistle had been frantically blown at the count of seven, and that Willard had been temporarily saved by the nonexistent bell. While Dempsey was struggling to make his way back to the ring through the frenzied crowd, Willard’s handlers had carried him to his corner and worked on reviving him. In what is undoubtedly the longest between-round rest period in a championship fight, Dempsey got no rest at all having been jostled about on his feet for the entire time. The second and third rounds were anticlimactic. Dempsey was arm-weary and dazed not only by the sudden turn of events but also by the realization that the $100,000 which he and Kearns had apparently won had been turned into a $10,000 loss. If Dempsey was dazed, Willard was more so. He was bleeding about the face, his jaw sagged open, his cheekbone was split, his nose was smashed, teeth were missing, and his once-white body was a mass of red bruises and welts. Although he was tottering all over the ring, he couldn’t be toppled. Grantland Rice described his performance as “one of the greatest exhibitions of raw and unadultered gameness ever seen.”

Between the third and fourth rounds Willard’s remaining strength ebbed away, one of his seconds tossed a towel into the ring, and without any doubt this time Jack Dempsey was the new heavyweight champion of the world.

Perhaps it was the confusion of the day or perhaps it was the heat that did it, but years afterward Dempsey recalled how that night he had a nightmare in which he dreamed Willard had knocked him out. He got out of bed, dressed, went down to the hotel lobby, and got a paper to be sure he really was the new champion.

Before we close this story, we must review some of the other outcomes of the day. On the whole it is a sad story, and most of the blame, rightfully or allegedly, was placed on the unconscionable weather.

Although the gate of $452,000 was a new high record it was far short of Rickard’s anticipated $1,000,000. He had expected to sell between $200,000 and $250,000 worth of tickets on the last day; he sold only $17,000. Of the approximately 21, 000 spectators in attendance, 19,650 had paid their way; the nonpaying customers included 300 policemen, 75 firemen, 600 ushers, 100 ticket takers, and 454 working newspapermen. The bulk of the attendance came from a distance; the heat wave melted the ardor of most of the boxing fans in the entire Great Lakes belt. Not counted in the above attendance figure were the several thousand more spectators in the arena at the finish than at the start of the bout. When Willard was apparently counted out at the end of the first round, hundreds rushed from the stands. Before they had hardly gotten outside the gates word came that Willard was going to start the second round. In the excitement ticket takers darted back with the fans, and following them came thousands who had been milling around outside the park.

For most of the concessionaires the big fistic event turned out to be a big fiasco. 80,000 of the fifty-cent programs were left over. A vendor who had invested $900 in peanuts had total sales amounting to $70.00. The city lost thousands of dollars on its parking lot with only a tenth of the spaces filled. Because of a story, allegedly true, which circulated throughout the arena, no one wanted to try the lemonade. The story: on the night before the fight, eccentric Battling Nelson in an attempt to cool off had taken a bath in one of the tanks of lemonade being cooled under the stands. The man who had paid twenty-five hundred dollars for Japanese cushions had not counted on the newspaper warnings about slivers and bubbling resin; everyone brought his own seat cushion. The cigarette concessionaire met a like fate; the fire commissioner had prohibited smoking in the arena. The intensity of the heat reduced the ice cream to an ocean of milk and spoiled the sandwiches by the time of the main event. The improvised dormitories had nothing but row after row of empty unused cots. The jinx appeared to hang on even after the fight. A Chicago wrecking company bought the arena, but it lost on the transaction when it discovered McLaughlin had built it better than its dismantling crews had figured. Even the motion picture censor got into the act when he prohibited the showing of the fight films.

Did anything good come out of this boxing cauldron? Whether the pulverized condition of his body was worth it or not, Willard did have his $100,000. Promoter Rickard was without a doubt now launched on his great career which was synonymous with the Golden Era of Boxing and which led to his purchase of the old Madison Square Garden and his subsequent building of the new one in 1925.

Dempsey went on to become one of the greatest, if not the greatest, of all heavyweight fighters. Before concluding his ring career he had participated in fights totaling a collective gate of $10,000,000.

And Toledo itself? It gradually recovered from the weird experience to become a great inland seaport, a city of culture and industry, and the leading glass manufacturing center in the world. However, to this day, local citizens shake their heads in amazement and amusement, chagrin and pride as the recall Toledo’s day in the sun.

Go back to Captain John's Custom Photo & Framing main page